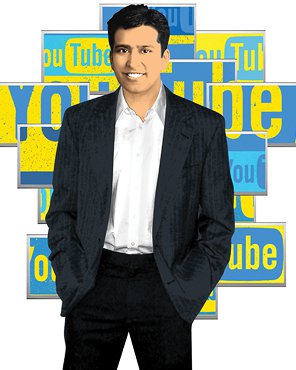

In 2008, when Shishir Mehrotra joined YouTube to take charge of advertising, the booming video-sharing service was getting hundreds of millions of views a day. YouTube, which had been acquired by Google in 2006, was also spending as much as $700 million on Internet bandwidth, content licensing, and other costs. With revenue of only $200 million, YouTube was widely viewed as Google’s folly.

Mehrotra, an MIT math and computer science alum who had never worked in advertising, thought he had a solution: skippable ads that advertisers would pay for only when people watched them. That would be a radical change from the conventional media model of paying for ad “impressions” regardless of whether the ads are actually viewed, and even from Google’s own pay-per-click model. He reckoned his plan would provide an incentive to create better advertising and increase the value for advertisers of those ads people chose to watch. But the risk was huge: people might not watch the ads at all.

Mehrotra’s gamble paid off. YouTube will gross $3.6 billion this year, estimates Citi analyst Mark Mahaney. The $2.4 billion that YouTube will keep after sharing ad revenue with video content partners is nearly six times the revenue the streaming video service Hulu raked in last year from ads and subscriptions. And that suggests Mehrotra has helped Google solve a problem many fast-growing Web companies continue to struggle with: how to make money off the huge audience that uses its service free.

In 2008, Mehrotra was working for Microsoft and hankered to have his own startup, but he agreed to talk to a Google executive he knew about working there instead. He decided against it—but that evening he kept thinking about how the exec was frustrated that most ad dollars go to TV, even though nobody watches TV ads. Yet at his Super Bowl party two weeks earlier, Mehrotra recalled, guests kept asking him to replay the ads. Was there a way, he wondered, to make TV ads as captivating as Super Bowl ads, every day?

The answer came to him in a flash. The next day, he had changed his mind about working at Google. After he tried his idea for skippable ads on a television project, the company asked him to bring the idea to YouTube.

YouTube was searching for alternatives to standard “pre-roll” ads, which performed poorly because viewers didn’t want to sit through a 30-second ad to watch a two-minute video. In 2010, Mehrotra’s alternative came to fruition as YouTube rolled out its TrueView ads. One type lets viewers choose from three ads. Another lets them skip an ad after five seconds; advertisers pay only if their ads are watched in their entirety, or for at least 30 seconds if the ads are longer than that.

Thousands of advertisers piled in. Now some 65 percent of ads inside YouTube videos are skippable. But YouTube has found that only 10 percent of viewers always skip ads, and viewership is 40 percent higher on videos running TrueView than on those with non-skippable ads. As a result, Mehrotra says, video viewed on YouTube brings in more ad revenue per hour than cable TV.

Thanks to Mehrotra’s ad model—and to Google’s crackdown on piracy of television shows and films—YouTube now attracts top-line content producers such as the nonprofit academic-tutorial producer Khan Academy, Paramount, and the NBA. Revenues paid to YouTube’s 30,000-plus video-making partners have doubled in each of the past four years. Thousands of partners get six-figure annual revenues from the ads, and a few take in tens of millions of dollars.

The result is a virtuous cycle. “The more money we bring in, the better content they produce, the more there is for viewers to watch, and so on,” Mehrotra says.

Now Mehrotra’s goal is to try to grab a big chunk of the $60 billion U.S. television business. But to do that, and fend off TV-content-oriented online rivals such as Hulu, YouTube has to become a bit more like conventional TV. To that end, it organized itself last year into TV-like channels, investing $100 million in cable-quality launches from Ashton Kutcher, Madonna, the Wall Street Journal, and dozens of others. More and more TV advertisers are being won over, says David Cohen, chief media officer at the media buying agency Universal McCann. “They’re getting marketers to think about YouTube as a viable outlet,” he says.

Mehrotra, who last year became YouTube’s vice president of product, envisions millions of online channels disrupting TV, just as cable’s 400 channels disrupted the four broadcast networks. “We want to be the host of that next generation of channels,” he says.

—Robert D. Hof