People often find robots baffling and even frightening. Leila Takayama, a social scientist, has found ways to smooth out their rough edges. Through numerous studies and experiments that look at how people react to every aspect of robots, from their height to their posture, Takayama has come up with key insights into how robots should look and act to gain acceptance and become more useful to people.

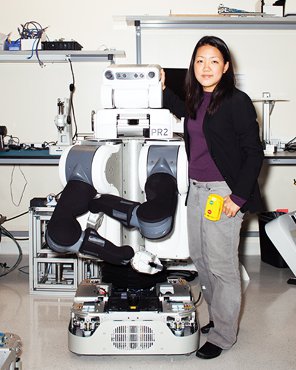

Takayama has had an especially big influence on the design of an advanced robot from Willow Garage, the startup she works for in Menlo Park, California. Called PR2 (see “Robots That Learn from People”), it’s an early prototype of a new generation of robots that promise to be indispensable to the elderly, people with physical challenges, or anyone who simply needs a little help around the home or office.

PR2 can fold laundry and fetch drinks, among other impressive tasks. But Takayama suspected that the nest of a half-dozen cameras originally perched on PR2’s head would alienate users. To find out, she turned to crowdsourcing, showing images of the robot head to an online audience recruited for the purpose. The results verified her concerns, and she successfully lobbied to jettison all but a few of the cameras, some of which were redundant.

More recently, Takayama has devoted effort to improving a robot called Project Texai, which is operated directly by humans rather than running autonomously. She ran an extensive field study to find out how Project Texai fit into the office environment of several different companies, coming by each office every two weeks to collect feedback and observe interactions between on-site staff and robots operated by remote colleagues. That study led to a surprising insight: “When you control a telepresence robot, there comes a point for a lot of people when they feel as if the robot is their body,” she explains. “They don’t want people to stand too close or touch the buttons on the screen.”

She also discovered that people in the offices ended up being less comfortable with Project Texai if they were allowed to dress it up. Personalizing the robot led people to feel more possessive about it and less accepting of the fact that someone else was controlling it. Project Texai should be personalized, Takayama concluded, but only by the “pilot,” and not by those who are around the machine. She also found that robot size can have a big impact on acceptance and is conducting a study to nail down the optimal height for Project Texai. Another key question: is it better to have the robot at eye level with a person who is sitting or standing?

Takayama is now conducting home interviews with the elderly and disabled to figure out which sorts of tasks would be most helpful to them. She predicts that someday soon, older people will employ personal robots to help them communicate with family and friends.

—Jessica Leber