Biotechnology & medicine

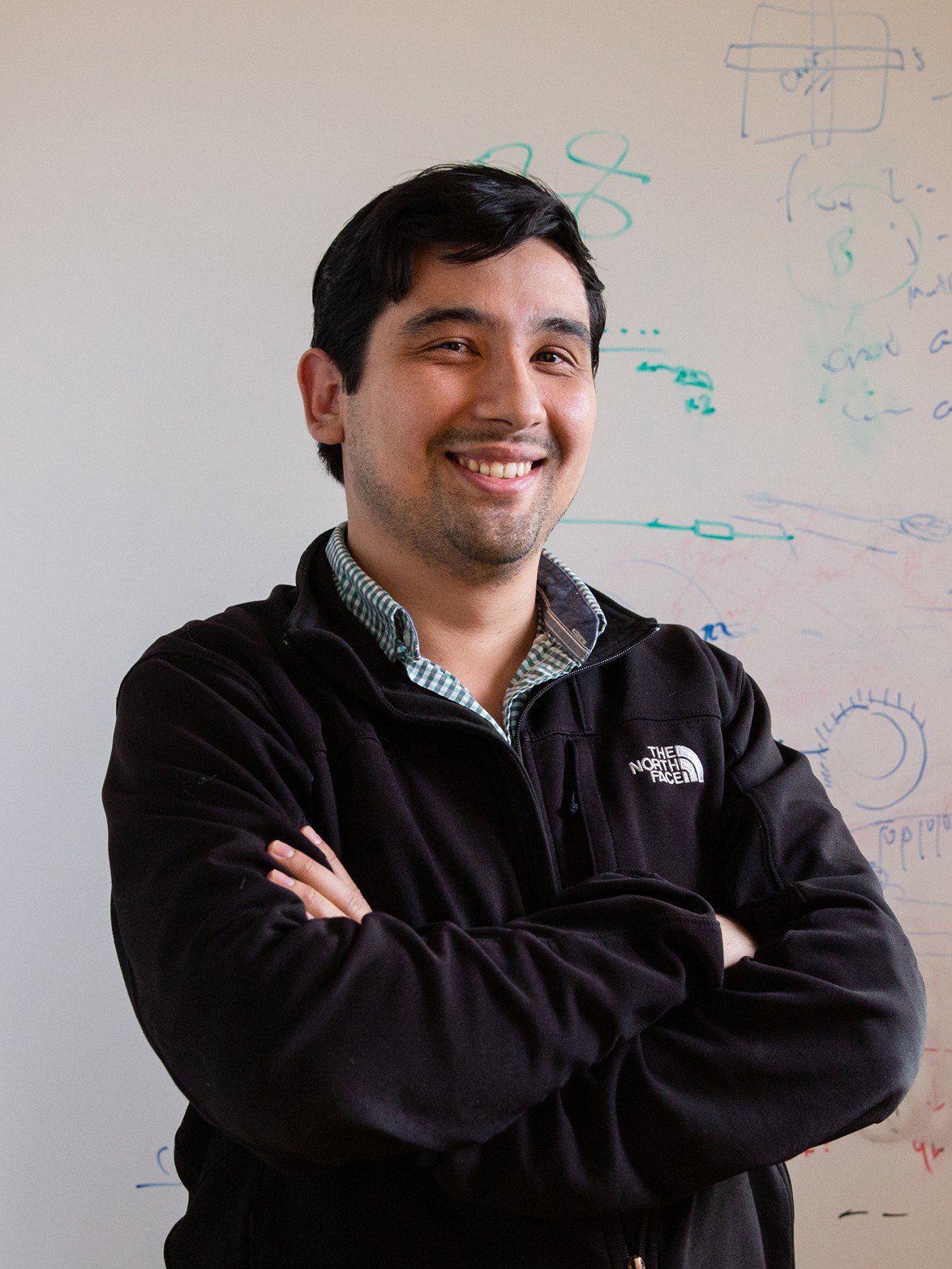

Jason Buenrostro

A tinkerer figures out how to tell which genes are active inside a cell

MENA

Mohamed Dhaouafi

Affordable 3D printed, bionic, and customizable prosthetics for children and youth

Global

Marc Lajoie

Programming white blood cells to fight cancer

China

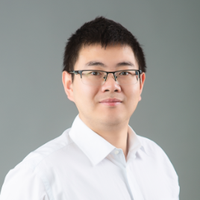

Zhiguang Wu

Created a micro-nano robot to accurately deliver drugs to hard-to-reach tissues

China

Lei Li

Understanding the human brain through photoacoustic tomography