"The digestive system is behind 40% of cancer related deaths in Chile. Bowel cancer is the second most deadly cancer, after stomach cancer, and the chances of survival for the millions of patients worldwide depend heavily on an early diagnosis. Detecting these forms of cancer involves a colonoscopy, in which a flexible tube is inserted through the rectum with a tiny camera called an endoscope. An expert, medical professional views the images captured during the procedure and tries to identify anomalies. The problem is that during the early stages, one of the telltale lesions of this type of cancer is small and flat, which makes it difficult to spot with the naked eye. ""Almost half of these lesions go unnoticed and, as a consequence, one out of every five colonoscopies fails to detect precancerous lesions"", the Chilean doctor Fernando Ávila explains.

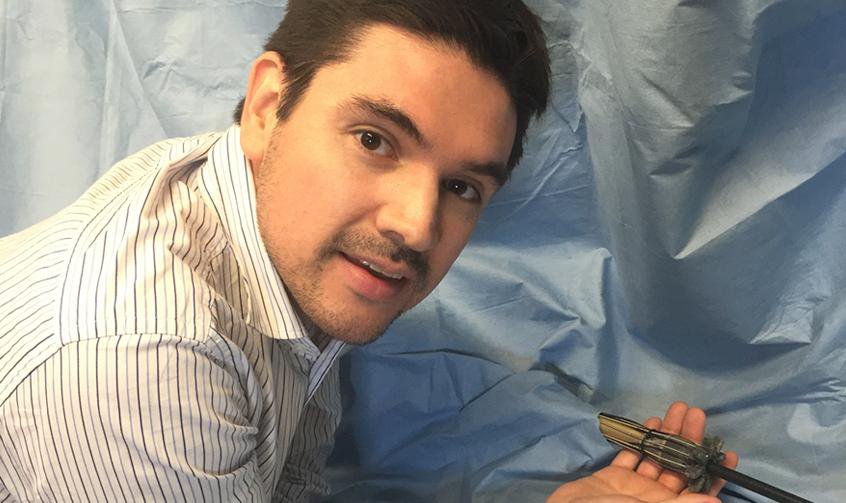

Ávila has developed a robotic device called EndoDrone that improves the chances of detection for even the most elusive cancers. The same device is also able to surgically remove the offending areas without subjecting the patient to a second procedure. Thanks to this breakthrough, Ávila, who also holds a master´s degree in Medical Robotics and Interventions Guided by Imagery from the Imperial College of London (United Kingdom), has been selected as one of MIT Technology Review, Spanish Edition´s Innovators Under 35 Chile 2016.

The EndoDrone is an accessory that easily adapts to any existing endoscope. Ávila´s approach consisted in using the endoscope, once inside the patient´s colon, as a train track upon which to travel. The device includes eight low cost sensors that rotate on their own axis. Once the EndoDrone has advanced to the end of the endoscope, it opens its sensors like an umbrella and begins to backtrack, rotating and mapping the colon´s internal tissue, millimeter by millimeter. Using the endoscope as a guide allows the medical professional to navigate the device through the digestive tract more easily.

EndoDrone´s sensors are very simple: just a few filaments of optical fibers that light up the tissue. The photons penetrate the multiple layers of tissue, bounce off and return to the device where they are detected by the optical fibers. In this way, Ávila obtains an ""optical signature"", or in other words, ""a measure of how some colors reflect more than others within the tissue"". This information allows the medical team to reconstruct a detailed, three dimensional map of the inside of the organ, through artificial intelligence techniques, which highlights suspicious areas. ""The sensor´s simplicity is not a limiting factor if you have a smart way of moving it around"", the young doctor explains.

Once these suspicious areas have been detected, the physician can move the endoscope to these spots, obtain a sample of the precancerous tissue (to be sent for analysis), or remove the tissue right then and there, without the need for a second procedure using a resection instrument integrated within the endoscope.

Other diagnostic techniques like blood tests and stool analysis (which can identify biomarkers) and endoscopic capsules, that the patient swallows to capture images as it passes through the digestive tract, lead the patient to undergo a colonoscopy to remove the problematic tissue. With Ávila´s device, this could all be accomplished at once, reducing costs, and saving time and eliminating inconveniences for the patient and physician.

""In Chile, we have a deficit of 5,500 endoscopy specialists, which we would need to in order to execute a real, colon cancer prevention program,"" Ávila points out. In the future, thanks to his device, perhaps such specialized staff will not be required for detection: a nurse or nurse´s aide could easily operate an EndoDrone. It could also be used to detect cancer of the esophagus, an area that Ávila considers easier to explore, since the esophagus is a bodily canal without folds."