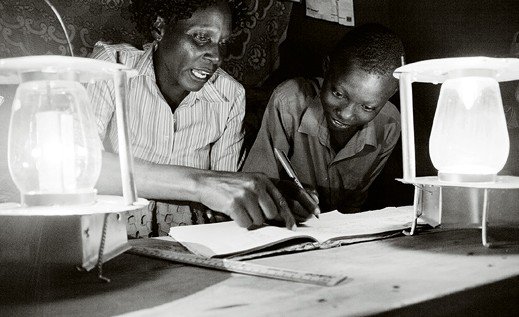

Kenya’s unreliable electric grid doesn’t reach Chumvi, a village about two hours southeast of Nairobi, where many of the 500 residents live in mud-walled, grass-roofed homes and eke out a living raising goats and growing kale, maize, and other crops. Yet an economic transformation is taking place, driven by an unlikely source—solar-charged LED lanterns. It can be traced to the vision of Evans Wadongo, 27, who grew up in a village much like this one.

As a child, Wadongo struggled to study by the dim, smoky light of a kerosene lantern that he shared with his four older brothers. His eyes were irritated, and he often was unable to finish his homework. “Many students fail to complete their education and remain poor partly because they don’t have good light,” says Wadongo, who speaks slowly and softly.

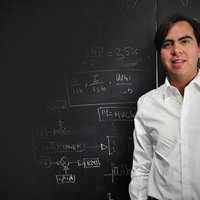

As a student at the Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology, he happened to see holiday lights made from LEDs and thought about what it would take to bring LEDs to small villages for general lighting. After taking a leadership training course from a nonprofit group, he designed a manufacturing system for portable LED lamps that could be recharged by sunlight. While many such lamps are already for sale commercially—and are increasingly making their way into villages in poor countries—Wadongo decided that his lanterns would be made in local workshops with scrap metal and off-the-shelf photovoltaic panels, batteries, and LEDs.

Wadongo feared that the technology would be less likely to take hold if the lamps were simply given to people who had no financial stake in them. But the lanterns normally each cost 2,000 Kenyan shillings (about $23), which is out of many villagers’ reach. So he uses donations (including proceeds from a recent exhibition of his lamps at a Manhattan art gallery, at which donors gave $275 apiece) to provide initial batches of lamps to villages. Residents are generally quick to see the value in the LED lamps because of the money they save on kerosene. Wadongo then encourages them to put the resulting savings into local enterprises.

The transformation in Chumvi began two years ago, when a woman named Eunice Muthengi, who had grown up there and went on to study in the United States, bought 30 lanterns and donated them to women in the village. Given that the fuel for one $6 kerosene lamp can cost $1 a week, the donation not only gave people in the town a better, cleaner light source but freed up more than $1,500 a year. With this money, local women launched a village microlending service and built businesses making bead crafts and handbags. “We’re now able to save 10 to 20 shillings [11 to 23 cents] a day, and in a month that amounts to something worthwhile,” says Irene Peter, a 43-year-old mother of two who raises maize and tomatoes. “Personally, I saved and got a sheep who has now given birth.” She also got started in a business making ornaments and curios.

As profits rolled in from new enterprises like these, the women who got the original 30 lamps gradually bought new batches; according to Wadongo, they now have 150. “Their economic situation is improving, and this is really what keeps me going,” he says, adding that some people are even making enough to build better houses. “The impact of what we do,” he says, “is not in the number of lamps we distribute but how many lives we can change.”

Wadongo is also changing lives with the manufacturing jobs he is creating. In an industrial area of Nairobi, banging and clanking sounds fill a dirt-floored shack as two men hammer orange and green scraps of sheet metal into the bases of the next batch of lamps (soon to be spray-painted silver). Each base is also stamped with the name of the lamp—Mwanga Bora (Swahili for “Good Light”). The three men in the workshop can make 100 lamp housings a week and are paid $4 for each one. Subtracting rent for the manufacturing space, each man clears $110 per week—far above the Kenyan minimum wage.

Some of the lamps are completed in the kitchen of a rented house in Nairobi. Three LED elements are pushed through a cardboard tube so they stand up inside the lantern’s glass shade. The LED elements, photovoltaic panel, and batteries are sourced from major electronics companies. Overall, the devices are rugged; the steel in the housing of the lantern is a heavy gauge. If a housing breaks, it can be serviced locally—and the electronic parts are easily swapped out.

Wadongo now heads Sustainable Development for All, the NGO that gave him his leadership training, and he is focusing it on expanding the lamp production program. It has made and distributed 32,000 lamps and is poised to increase that number dramatically by opening 20 manufacturing centers in Kenya and Malawi. Wadongo says that teams in those centers will independently manufacture not only the lamps but “any creative thing they want to make.”

—David Talbot