Biotechnology & medicine

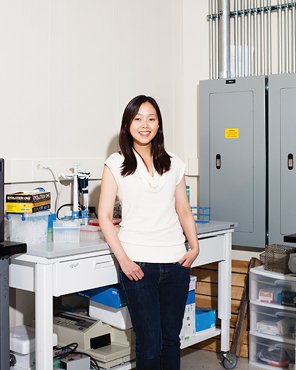

Christina Fan

Prenatal testing for genetic conditions from a sample of the mother’s blood

Latin America

Juan Sebastián Osorio Valencia

Personalized medical devices for an specialized medical care

Latin America

Marcelo Martí

New approach in the search for effective TB treatment

Europe

Héctor Perea

Creating implants with the patient's own cells

Global

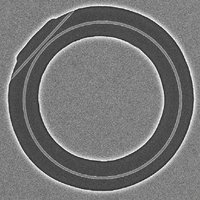

Ryan Bailey

Shining a light on faster, cheaper, more accurate medical tests