Biotechnology & medicine

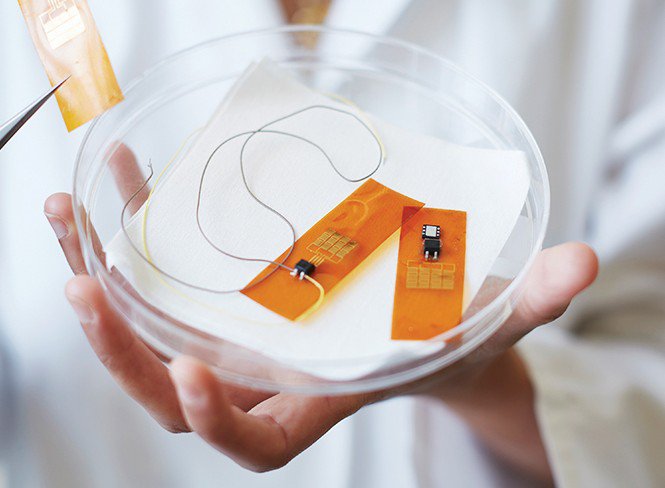

Canan Dagdeviren

A master of flexible sensors and batteries sees opportunities for a new class of medical devices.

Photos by Christopher Churchill

Asia Pacific

Ruey Feng Peh

Advent Access: Preserving Vascular Health, Reducing Dialysis Cost

Europe

Katarzyna Nawrotek

Her personalized, biocompatible implants can regenerate and reconnect damaged nerves

Global

Jini Kim

A stint helping the government altered her view of her health-care business.

Asia Pacific

Rikky Muller

Electronics that Heal and Connect the Brain