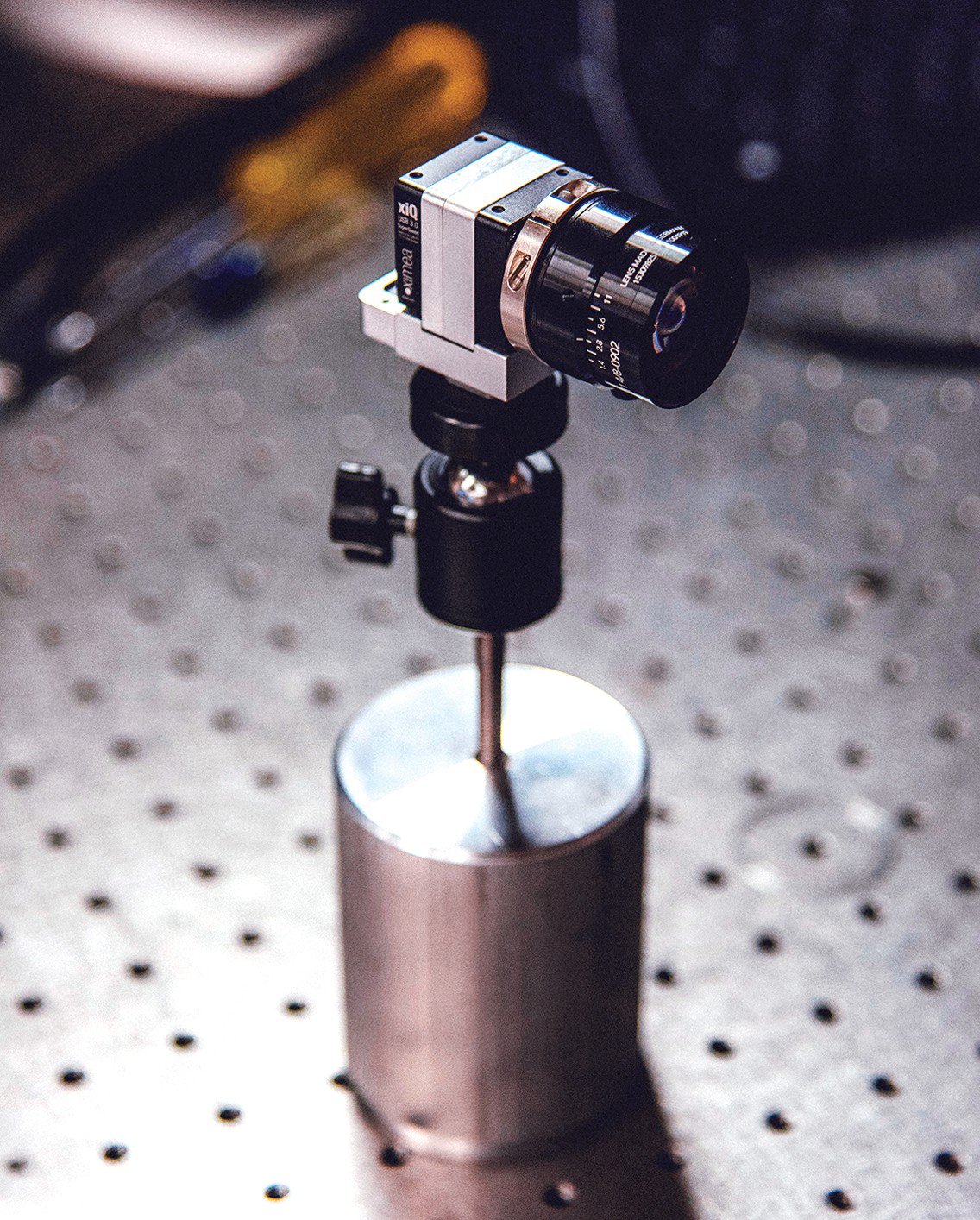

Computer & electronics hardware

Alex Hegyi

A new type of camera could let smartphones find counterfeit drugs or spot the ripest peach.

Photos by Damien Maloney

Latin America

Katia Canepa

Combining beauty products with electronics to create wearables that give users "superpowers

Latin America

Emilio de la Jara

Isolated communities can gain access to cheaper, sustainable energy thanks to his hydraulic system

Asia Pacific

Joseph Fitzsimons

Secure Computation in a Quantum World

Europe

Jordina Arcal

Eating disorders, obesity and childhood psychosis can be controlled with her health apps